Why We Need Women-Led Cities

mars 5, 2018 — The Big Picture

Urbanism remains a niche and even “nerdy” subject by many accounts, but I think that’s an outdated mindset. With the vast majority of humans living in cities worldwide — for the first time ever — the time has come to make cities front and center in our conversations on the future.

The reason why this is such a big deal is in part because cities are our own unnatural habitats — built by us, for our fellow human beings.

Let that sink in for a moment: like an artificial Arctic habitat for a polar bear in a zoo, our cities are manufactured constructs that we have haphazardly put together over time with what could only be considered (at times) reckless abandon.

Without a concerted effort toward evidence-based design and humanist policy, we are creating habitats that do a disservice to our fellow humans at best, and literally kill them at worst.

By bringing this into the mainstream, I hope to raise awareness of how we are impacted by our environment — and how we know what works well in many areas of our city building.

But before we can advocate for humanist cities for people, I also want to raise awareness of another key point in our urban history: the fact that since we began making them, our cities have apparently always been designed and managed by men.

That means everything you see out your window, in whatever city you’re in, was imagined and made real by one half of our species.

If you’re a woman, like myself, we are the minority in making an impact on our own habitat. In other words, our right to the city has been suppressed. For a person of color, in some places the situation is even worse.

Late last year, I wrote this piece for Next City summarizing some of my journey to this realization. I wanted to lay the groundwork and research I’ve conducted for a project that intends to address this inequity: The Women-Led Cities Initiative.

The article outlines some of the “ah-ha” moments I had in the last year and a half, especially since experiencing a sexist incident at a former workplace. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the realization that much of my higher education was from the perspective of mostly white men, or that our cities are primarily shaped by men and what that means for me as a woman, until very recently.

Truthfully, I’m one of the lucky ones — I’ve never been assaulted physically or sexually while walking down the street. But the city impacts every way that I move and live as a woman whether I recognize it or not. I’ve resisted the urge to “hollaback” in one of the rare moments that I’ve been cat-called, for instance, because of a fear of assault. As a woman, the threat to your life by men on the streets (not only in your relationships) is, to put it lightly, a pretty big deal.

It’s not something I used to think about, but as they say: once seen, it cannot be unseen. And for the entire city itself to be created and controlled by men — well, I don’t even know all the ways that it impacts me on a daily basis at this point.

The thing is, I come to feminism late. For the longest time I didn’t even think of myself as gendered one way or the other. My mom was basically the head of the household, but she also stayed at home in order to raise us five kids (that number has risen to seven, going on nine if you count upcoming adoptions, by the way). As the oldest, I was more concerned with being a second mother, as well as finding ways to escape the chaos of my siblings (and foster children, and innumerable pets) through explorations in the woods, schooling, and video games.

It took me 32 years to get to a point where I could even call myself a feminist, after hearing so much about the negative assumptions people will have if you ascribe to the term. Wearing makeup and doing my hair was an equally strange struggle to get on board with.

I mention this because I want to make it clear why I’ve decided to pursue this goal. When you realize that your passion (i.e. cities) is essentially a foreign object, and how bad others have it even compared to you, I believe it’s imperative to act.

This is my cause, because I understand it’s the one that I’m most suited to have an impact on. This is my passion, because I believe that the time is right to raise awareness of sexist implication in this, my nerdy subject called urbanism.

But I obviously don’t have all the answers, which is the beauty of the tight-knit global network of urban aficionados. Once I started exploring this subject with the friends and colleagues I’ve made from past conferences, academia, and social media, I realized that the missing element is a shared platform. If we can bring women together from all fields of urbanism, whether they have an existing group or organization or not, we can work together to tackle this daunting issue. It’s the only way it can succeed.

More specifically, the goal for Women-Led Cities project is threefold:

- Expand the conversation through evidence-based research, thought leadership, and speaking up in print and in person.

- Create a program of working conferences and open-source event programming that can be implemented in any city to start the process of being women-led.

- Provide a platform for women working worldwide to make our cities better by and for women and girls, in an online format and international conference.

Once we add or increase this missing voice we can strategically hope to impact our cities and make them more equitable in so many other ways — for people of all ages, backgrounds, experiences, incomes, and gender identities. I won’t say this isn’t a strategic move because that would be dishonest.

But this is in no way against men, and for that matter will be very much with them. This is just about giving one side a leg up, and the opportunity to have the same amount of seats at the table for the creation and management of our shared urban homes. Without it, it’s an injustice.

If women have never been able to have a major impact on our urban environments — throughout our entire human history — then I’d like to start there. We have no idea what that could look like, but I have high hopes considering the breadth of experiences women have had as compared to their male counterparts and the evidence we have so far.

And with the way our cities are rapidly increasing in size and popularity, while simultaneously facing challenges like climate change and how best to implement smart city technology, it’s going to take all of us. How else can we expect to make the best habitat for all of us — without all of us involved?

Put simply, we need women-led cities because our cities need us.

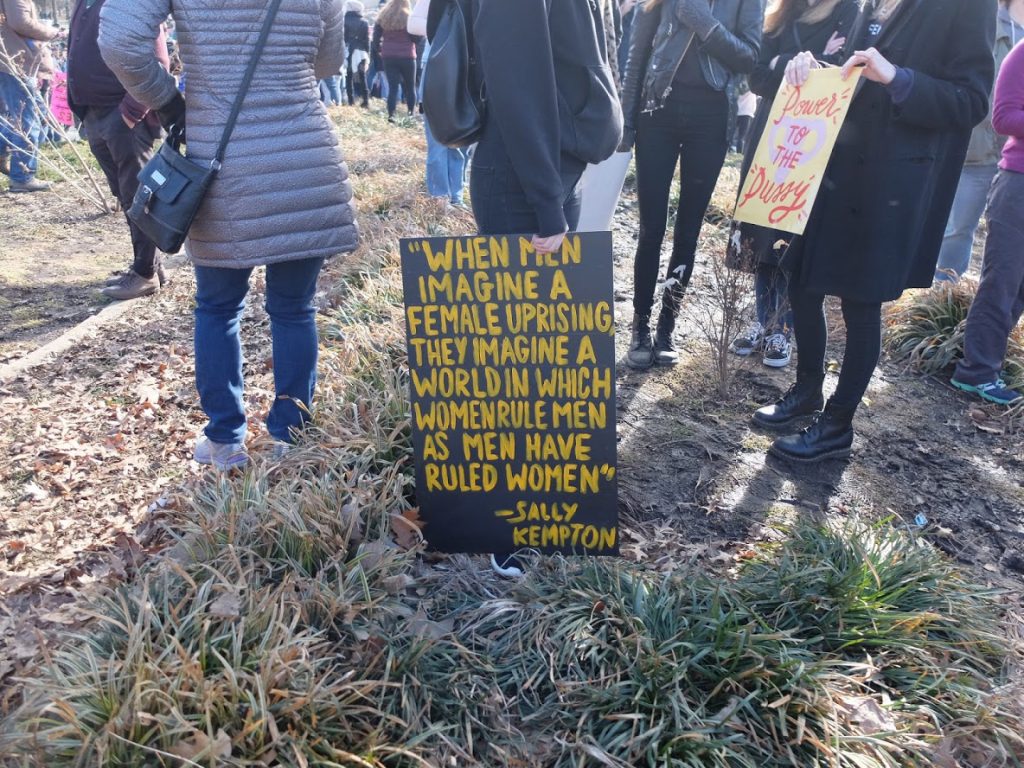

All photos were taken during the Women’s March in Philadelphia, 2018 by Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman.