How Millennials are Retrofitting North American Suburbs

June 5, 2020 — The Big Picture

In 2000, the leading edge of the Millennial generation was still in high school, the youngest in diapers. In 2020, Millennials comprise a big chunk of the American workforce, and are reflective of profoundly diversified suburban demographics. Over these twenty years, I’ve been researching and writing about why it’s high time to “retrofit” the suburbanized landscapes in the metropolitan areas of northern America into new, more progressive and resilient forms, and how building architects, landscape architects, urban planners, progressive developers, and allied visionaries are already contributing to this work. The Millennial generation is helping to get it done.

In this moment, they are jettisoning outdated stereotypes comparing “the” suburbs (read: static, homogeneously white, and middle-class) to cities (dynamic and diverse). They know, from lived experience, that various groups are found everywhere: from rich to poor; young to old; white, black, and brown; “native” born and immigrant. This is not to say that suburbanized built environments are designed to meet current needs and desires. However, pockets of retrofitted mixed-use, higher density “walkable urbanism” increasingly appear in sprawled landscapes, like Belmar, built on a dead mall site in Lakewood, Colorado. These newly configured neighborhoods, on land formerly dedicated exclusively to industrial and commercial uses, such as shopping malls surrounded by parking lots, attract both Millennials and “Perennials,” as Laura Carstensen has named the cohort of older adults seeking out a rejuvenating third or fourth act, as they reap the longevity dividend of public health and medical advances.

In a forthcoming book featuring dozens of new retrofitting suburbia case studies, Ellen Dunham-Jones and I (co-authors of Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs) identify six major challenges for raising the bar on future suburban retrofitting efforts that recognize imperatives to improve environmental resiliency and redress inequities and injustices in suburbia. The challenges are:

- 1. Disrupt automobile dependence

- 2. Improve public health

- 3. Support an aging population

- 4. Leverage social capital for equity

- 5. Compete for jobs

- 6. Add water and energy resilience

While the vast majority of the northern American population currently lives in suburban areas—representing all income levels, all ages, all races, all countries of origin—their lived experiences differ greatly. The jobs and social equity challenges, in particular, center on Millennials of all backgrounds, and the Gen-Zers following them into the workforce. In the United States, in particular, as the economy continues to undergo dramatic restructuring, brought into stark relief by the staggering job losses and accelerated retail bankruptcies precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, suburban areas will struggle to maintain a synergistic balance between high and low wage jobs. Once the pride of companies who chose to relocate from fusty old central business districts into custom-commissioned showcases of architectural invention and display, suburban office parks and corporate campuses are increasingly aging and abandoned. They can be creatively retrofitted to attract and retain younger cohorts of workers. How? Consciously redesign them to incorporate elements of urbanism as workplace amenities. Break up the building shells to lease to a more diverse set of small businesses.

Or, remodel and lease or sell outmoded and surplus commercial buildings to higher education institutions. Increasingly enrolled in college as adult learners, Millennial students, have vastly differing needs from traditional college students who show up on campus fresh out of high school. They are shifting patterns in higher education. In response, community colleges convert old malls into branch campuses, as Austin Community College did at the old Highland Mall in north Austin, Texas. In the context of COVID-19, colleges are likely to become more reliant on online and hybrid instruction, with small, distributed higher ed hubs needed for elements of instruction such as science labs and design studios requiring in person meetings.

As for leveraging suburban social capital to increase equity, I reiterate that suburbs are not, and never have been, homogenously the same. With few exceptions, however, they exhibit high degrees of socio-political fragmentation and racialized segregation. They’ve been systemically structured that way by private and public means—restrictive property deeds, exclusionary zoning codes, discriminatory bank lending, federal subsidies—for several generations now, especially in the U.S., to persistent effect.

Social Capital is defined as relational networks of civic trust and social cohesion in a given society, based on shared norms and values, enabling that society to function effectively. Supportive social connections can provide pathways for specific individuals to increase their happiness and wellbeing, and to access economic opportunity. Robust social infrastructures are vitally important to building resilience in suburban areas where poverty and inequality are increasing, and injustices persist. How can retrofits raise the bar on this challenge in ways that leverage Millennial lifestyles and preferences? To name just a few:

- Support the flourishing of unique, locally owned businesses in reinhabitation-type retrofits of commercial spaces in so-called ethnoburbs, suburban places where the newest immigrant groups concentrate.

- Add new housing types and choices to redevelopment-type retrofits—made more affordable through smaller unit and lot sizes or subsidies, and with transit access and other “urban” amenities.

- Ensure equitable access to an enhanced civic realm in regreening retrofits, by adding ecologically designed plazas and healing green parks.

The best way to support my argument, perhaps, is with examples. Each demonstrates ways these challenges are being met.

Bell Works, Holmdel, New Jersey

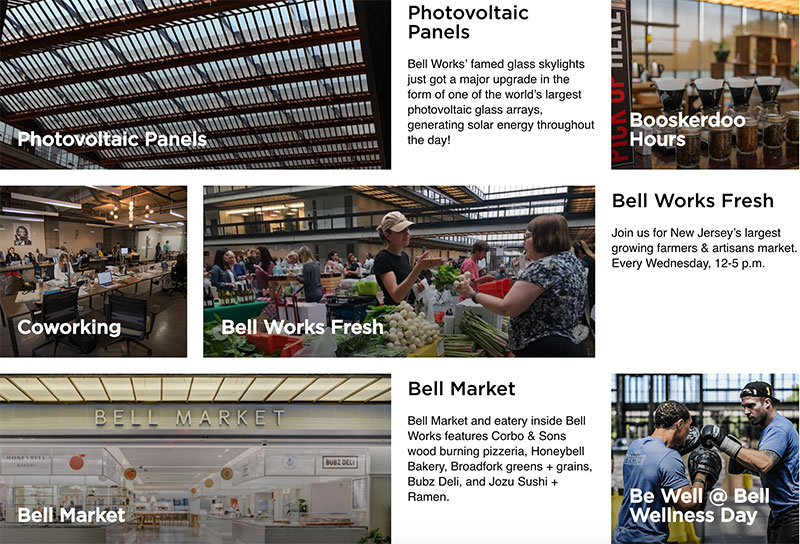

First up, Bell Works. Famed modernist architect Eero Saarinen’s stunning corporate research campus for Bell Labs in suburban New Jersey was THE place where all kinds of telecommunications technologies were developed, from the transistor to solar cells and cellular technology. It has been reinhabited by Somerset Development into what’s been dubbed a “metroburb.” Instead of one corporation, small spaces on the six floors are leased to dozens of startups and other companies with a Millennial-heavy workforce. Reconceived as an indoor “Main Street,” the building’s stunning, quarter-mile-long skylit atrium hosts regularly programmed activities such as a farmers market, and is faced by a branch public library, Montessori school, hairdresser, and food hall.

Wyandanch Rising, Town of Babylon, New York

Wyandanch Rising is an ambitious retrofit, many years in the making, comprised of subsidized rental apartment buildings flanking an ecologically designed civic green, with a seasonal ice-skating rink. The site of cleaned up brownfields and parking lots is next to a tiny and formerly little used commuter rail station, since replaced with a gleaming new structure. The hamlet of Wyandanch, majority African American, had been named the single most distressed community on Long Island. Much effort by environmental justice advocates and urban planners went into building a robust network of trust with dozens of civic and religious groups. Residents in the new apartments include many female-headed family households. Local residents benefit directly from a jobs training program in the construction trades.

La Gran Plaza de Fort Worth, Texas

Seminary South Shopping Center was built on a drained lake in 1962 by the Homart Development Company, a subsidiary of mega-retailer Sears, now so troubled. Today, it’s a highly successful Hispanic themed mall called La Gran Plaza de Fort Worth, with a 120,000 sq. ft., three-level mercado, functioning as a local business incubator. La Gran Plaza regularly hosts events geared toward young people and families, such as Mexican wrestling in the atrium and huge fiestas in the parking lot.

Featured photo by Maximillian Conacher on Unsplash.