Biophilia and Urban Wellness

juillet 6, 2021 — Uncategorized, Highlight

By Andrew Snowhite and William Browning.

Biophilia is the innate human connection to nature, and cities around the world are discovering that it is more than just a feel-good notion. Creating experiences of nature in the urban environment has measurable physiological, psychological, and economic benefits. Streetscapes, parks, rooftops, and stormwater systems all offer opportunities for meaningful connections to nature.

Trees are a wonderful example; implementing strategies to preserve and increase the number of trees in a city has multiple benefits. In Washington, DC, the Casey Trees Endowment found that planting more street trees lowers heat island effect and helps reduce stormwater runoff. Street trees increase the willingness to pay for retail general by 25% and specialty retail by 15%. A public health study in Toronto found that having ten more trees per block on a street created a health benefit equivalent to increasing incomes by $10,000 with an equivalency of people being seven years younger. In Barcelona, a study involving 2,600 elementary age school children concluded that separate from demographics, having more tree canopy in the school yard led to a measurable increase in cognitive development over the course of a year.

The Power of Open Space

Creating, maintaining, and prioritizing parks and open spaces are important strategies for connecting to nature. In Japan, research into the experience of shinrin-yoku or “forest bathing” found participants had lower cortisol levels (a stress hormone) after walking or sitting in urban parks for 15 minutes versus walking or sitting on an urban street. In the Netherlands, a study of national health care system data found that independent of demographics, people living near parks and open space are healthier.

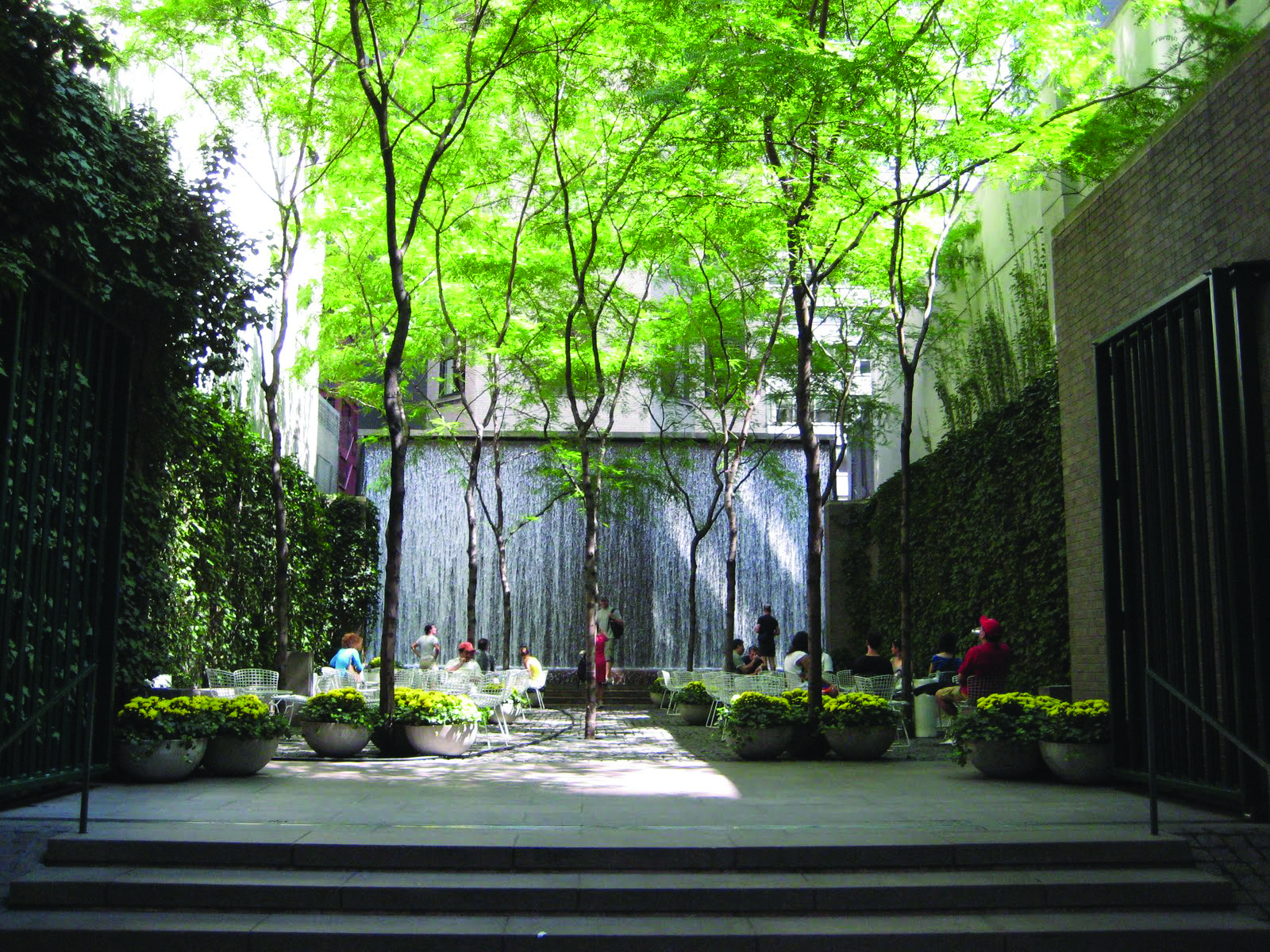

Parks are effective regardless of their size. In 1967, Paley Park in Manhattan at 30 feet by 90 feet was the first of what are now called “pocket parks.” The ivy walls and dappled light of the honey locust trees create a pleasant space, while the prominent water wall enlivens the park and masks street noise. On an even smaller scale, the “parklet” movement of converting street parking spaces into mini parks that started in San Francisco has now spread around the world. The parklets can be permanent or temporary, as in Vienna, Austria, where restaurants can rent adjacent parking spaces on their street to expand their summer dining space.

Utilizing abandoned infrastructure is another means to increase urban wellness, like the aging viaduct that was converted into the linear park La Promenade Plantee in Paris. That park inspired the conversion of a retired elevated freight line into the Highline in New York City. The Highline transformed the real estate market on the west side of Manhattan, provided a new recreation amenity to residents, and is now the second most visited attraction in the city. Vitoria Gasteiz in the Basque Country turned a series of railroad beds and stream corridors into a connected park system that runs through the fabric of the city. Similarly, the Beltline in Atlanta, Georgia will eventually connect a series of parks encircling the city. Conversions, if planned correctly, also support neighborhoods without causing historic inequality issues relating to housing and jobs. A large-scale open space community program led by The Trust for Public converted asphalt school yards into neighborhood parks at over 100 New York City schools!

Green Infrastructure

Green roofs reduce heat island and stormwater issues and if accessible are powerful biophilic design strategies. Some of the earliest research in biophilia indicated that a view to nature improves healing and reduces the length of hospitalization. Khoo Teck Puat Hospital in Singapore has a rainforest garden through the middle of the site, which is visible from patients’ beds, and an organic garden on the roof of the clinical wing of the hospital. The garden is run by local residents and the food is used in the hospital kitchens and local homes. Rooftop farming is catching on in many places, such as the rice paddy on the Mori Roppongi Hills Complex in Tokyo, and the commercial roof farms run by Brooklyn Grange in New York City. Not only is fresh and healthy food produced by and for locals while increasing available open spaces, but also carbon emissions and pollution issues relating to building cooling and transportation are mitigated.

Stormwater control systems are another opportunity to leverage biophilia. Portland, Oregon uses a network of rain gardens, green streets and parks to control stormwater. Tanner Springs Park in Portland’s redeveloped Pearl District creates wildlife habitat, controls local stormwater, and serves as a popular park and gathering space in a dense urban area. The City of Philadelphia determined that building a network of green roofs, rain gardens, and stormwater capture parks was less expensive than digging up the city to install a separated sewer system. In the town square in the medieval core of Hannoversche Munden, Germany, a sculptural water feature is used to control stormwater and create an interactive space for residents.

Using open spaces to protect and restore native biodiversity benefits human and natural residents and visitors. In Wellington, a central park was fenced to exclude cats, rats, and dogs to successfully restore habitat for extirpated native New Zealand bird species. Not only did this help increase bird populations, but it also provided urban birders a new observation hotspot. Wellington also cleaned its harbor to the point that it now supports a snorkeling and scuba trail that is accessible from walk-in points on the inner-city waterfront.

The idea of extending accessible open spaces to enhance human and ecosystem health is catching on in other parts of the world too. Palm Beach County in Florida created the Phil Foster Park snorkeling and diving trail, a series of underwater artificial structures that attract marine life and subsequently residents and tourists too. Similarly, an innovative Highline-type project is underway in Miami, Florida called “The Reef Line” that is creating a seven-mile-long underwater public sculpture park, snorkel trail, and artificial reef.

City-Scale Biophilia

Some cities are taking a holistic approach to biophilia; Singapore has adopted the goal of being a “City in a Garden.” This effort has many components including converting concrete water ways into naturalized parks, establishing wildlife corridors through urban areas, and developing a system to measure and monitor biodiversity. The city also requires new multistory buildings to include a horizontal planted area that is larger than the footprint of the building. The concept is called Green Area Ratio, which is calculated like the more familiar zoning tool of Floor Area Ratio. The result is extraordinary buildings like the ParkRoyal on Pickering. A hotel and office building with a Green Area Ratio of 2.7, it set a new design standard for the brand and the city. The hotel building now supports a higher level of biodiversity than the adjoining park!

The planned community of Reston, Virginia was designed with biophilia as a core tenant of the masterplan. This is a strategy that should be considered for any new urban development, especially new cities. Reston’s founder Robert E. Simon, Jr. codified this concept in the late 1960s in one of his “Seven Goals”: “That beauty – structural and natural – is a necessity of the good life and should be fostered.” Fifty years later this vision ensured that 11.4% of Reston’s 7,000 acres is meadows, wetlands, and urban forests and that tree canopy covers over 50% of the total area. Over 55 miles of paths connect Reston’s natural spaces to its residential, commercial, and recreational areas. Nature, and its ease of accessibility, is a key reason that it is now one of the most vibrant suburbs of Washington, DC, which is reflected in its thriving residential and commercial real estate markets.

Clearly, there are numerous benefits from integrating biophilia in urban settings, and everyday cities and communities are developing and implementing new programs and best-practices. The Biophilic Cities Network is a wonderful resource for learning more about what cities around the world are doing to connect their citizens to nature. Biophilia also is a valuable tool at all scales from individual rooms to entire buildings, as described in the new book: Nature Inside, A Biophilic Design Guide.

Andrew’s professional approach to urban planning and sustainable design was informed by the embedded biophilic design elements he experienced throughout his childhood while growing up in Reston.

(1) Deutsch, Barbara, Benefits of Street Trees, Casey Trees Endowment, Washington DC TK

(2) Wolf, Kathleen L. 2005. Trees in the small city retail business district: comparing resident and visitor perceptions. Journal of Forestry. 103(8): 390-395.

(3) Kardan, O., Gozdyra, P., Misic, B. et al. Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Sci Rep 5, 11610 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11610

(4) Dadvand P, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Esnaola M, Forns J, Basagaña X, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Rivas I, López-Vicente M, De Castro Pascual M, Su J, Jerrett M, Querol X, Sunyer J. Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015 Jun 30;112(26):7937-42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503402112.

(5) Tsunetsugu, Yuko & Lee, Juyoung & Park, Bum-Jin & Tyrväinen, Liisa & Kagawa, Takahide & Miyazaki, Yoshifumi. (2013). Physiological and psychological effects of viewing urban forest landscapes assessed by multiple measurement. Landscape and Urban Planning. 113. 90–93. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.01.014.

(6) Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P., de Vries, S., & Spreeuwenberg, P. (2006). Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Dealth, 60(7), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.043125

(7) The Trust for Public Land. “Asphalt Lot Transformed into a Student-Designed Play Space at P.S. 33.” Press Release. 25 May 2011.

(8) Biophilic Cities. (n.d.). Reston, Virginia. https://www.biophiliccities.org/reston