The High Cost of Ignoring Our Infrastructure

mai 31, 2016 — Uncategorized

“We need to ask ourselves: what is the cost of deferred investment and maintenance in infrastructure?” Jeffrey DeWitt, CFO of Washington, DC asked 150 thought leaders gathered in New York with the shared goal of exploring and identifying new ways of financing urban infrastructure. The answer to his question is clear. The cost of ignoring urban infrastructure needs today may spell catastrophe for cities – and government coffers – in the future.

Cities around the world are struggling to find ways to pay for water and wastewater treatment plants, roads and transit, waste disposal, electricity, schools, hospitals, and digital infrastructure. Traditional methods of paying for infrastructure (taxes, user fees, and transfers) are falling short of the trillions of dollars needed worldwide each year. At the same time, new actors are coming forward with innovative infrastructure financing techniques – crowdfunding, green bonds, social impact bonds, land value capture, and more. On May 9, 2016, NewCities hosted Innovations in Urban Infrastructure Financing, an event focused on financing techniques for various types of infrastructure in a range of cities around the world. Five key themes stood out.

First, there is a lot of money in the private sector that can be tapped into for infrastructure projects and that can generate significant returns. According to Julie Kim, author of the Handbook on Urban Infrastructure Finance, governments currently pay for 92 percent of infrastructure costs. The rapid pace of urbanization has put increasing pressure on governments to spend heavily on infrastructure. Meanwhile, trillions of dollars in the private sector available for investment are not being used. It is time to explore the barriers to private sector investment in municipal infrastructure and find ways to overcome them.

We need to ask ourselves: what is the cost of deferred investment and maintenance in infrastructure?

Second, financing and funding are not one in the same. Financing refers to the upfront capital costs to build infrastructure. Funding refers to the future revenue stream to repay the financing (for example, taxes user fees, and intergovernmental transfers). Even if cities can come up with financing arrangements through borrowing or public-private partnerships, they still have to find revenues to pay back the money they borrow. When it comes to funding, the importance of charging the right price for services cannot be stressed enough. When users do not pay the full cost, they demand more than if they had to cover costs. This over demand is for underpriced services, which leads to more expensive infrastructure than is economically efficient or justified.

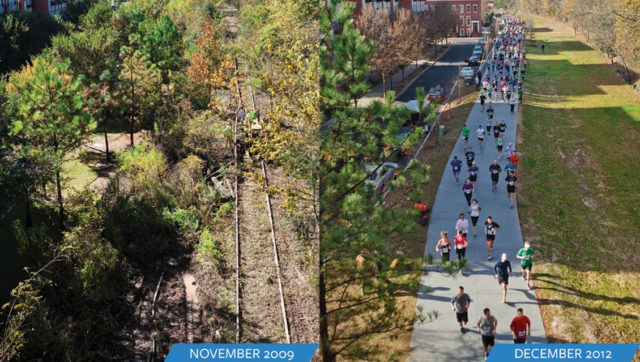

Third, there is merit in tying funding mechanisms to the value of land. Examples include land value capture taxes such as tax increment financing, and CEPAC bonds, which are sold to developers in return for additional development rights in some Brazilian cities. It was argued that at least some of the increase in land value driven by infrastructure investment or regulation changes should be funneled back to the governments paying for that infrastructure. Land value capture recoups some or all of that unearned increment in private land values. For example, the Atlanta Beltline Project, represented at the event by their Director Chuck Meadows, cost USD $13 million to build and led to $775 million in new private development.

Fourth, the public can play an important role in paying for infrastructure through mechanisms such as ballot initiatives or crowdfunding. Ballot initiatives are used in many US cities to raise funds to pay for transit and other infrastructure. Crowdfunding connects entrepreneurs looking to raise capital with investors who are willing to invest small amounts through web-based platforms. One major initiative was demonstrated by Kristian Koreman, founder of Studio Zus, which successfully crowdfunded a pedestrian bridge in Rotterdam, connecting various areas of the city otherwise separated by highways. Involving the public is not just about finding money to pay for infrastructure; it is also about civic engagement, public oversight, and transparency. Ultimately, infrastructure users have to pay for it through user fees or taxes and they need to be involved in decisions about what infrastructure should be provided and how they should pay for it.

Involving the public is not just about finding money to pay for infrastructure; it is also about civic engagement, public oversight, and transparency.

Fifth, urban governance and leadership are important aspects of infrastructure funding decisions. Urban governance refers to the process through which democratically elected local governments and the range of stakeholders in cities (business associations, unions, civil society and, of course, citizens) make decisions about how to plan, finance, and manage the urban realm. Regional governance is an issue for infrastructure that crosses municipal boundaries – how do you coordinate infrastructure when there are many fragmented jurisdictions involved? Several presenters talked about the importance of leadership of individual people who acted as champions in making projects happen – political leaders, bureaucrats, or community leaders.

Cities everywhere need to provide basic infrastructure to meet the demands of a growing urban population; innovative approaches are needed to reduce the infrastructure gap. Innovations in Urban Infrastructure Financing highlighted many of these innovative approaches giving us much food for thought going forward.