Climate Change and Human Mobility

janvier 28, 2020 — The Big Picture

“Open your eyes and look within: Are you satisfied with the life you’re living? We know where we’re going; We know where we’re from. We’re leaving Babylon, y’all! We’re going to our Father’s land.” Exodus – Bob Marley

Beyond the Book of Exodus reference in Marley’s song, the term exodus has a broader context in relation to climate related migration. The term is originally derived from the Greek word exodos meaning a marching out or going out now applies to the tens of millions of people around the world impacted by sea level rise, extreme heat, and flooding. From the scale of the individual to larger networks of people will be making the difficult decision to leave their homes, lands, and neighborhoods in order to survive the impacts of climate change. Where will they go? What will they do? How will they transition? These are among the questions being asked as countries react to depopulation, adaptation, and the increasing flow of people across political borders. With the coming climate exodus, can the mass migration of people be used as a catalyst for positive change for urbanity on higher ground?

The United Nations ruled recently that refugees fleeing the impacts of climate change cannot be sent back to their home countries. Climate change is projected to displace tens of millions of people. Both policy and planning are needed to not just accept people but nurture and catalyze their success through education, counseling and development of support networks at host sites. The United States has tremendous urban infrastructure that could be adapted.

A 2017 winning design competition entry funded by the Rockefeller Foundation as part of the 4th Regional Plan for the New York, New Jersey, Connecticut Region, provided a turning point in my strategic approach to managing climate change impacts. Working together with Professor Rafi Segal and his colleagues at MIT, we recognized the need to reconsider our relationship to the coast and develop a new Coastal Land Management Zone (CLMZ). This thinking was not new to me. My practice DLANDstudio was founded in 2005 with a focus on climate impacts on urban infrastructure. We proposed and built coastal landscapes in New York City with projects such as the Gowanus Sponge Park, MoMA New Urban Ground Plan for Lower Manhattan, NY Rising, and Marshes wetland mitigation bank. These projects transformed the water line into a hybrid ecological zone that manages upland flooding, reduces combined sewer overflow, and reduces storm surge impacts. What was different after a decade of work was a recognition that adaptation in-place was, in many situations, only a short-term answer.

Our study examined three communities of different population densities, demographics and geomorphology along the coast of New York and New Jersey: Seabright NJ, Mastic Beach NY and Jamaica Bay NY. What the sites share is a location in FEMA Zone A flood plains. The once dynamic landscapes were hardened by the promise of development and the engineering technology in the Post WWII era. Seventy years after Levittown became an archetypal model of the American dream of a house with a lawn and white picket fence, climate change is now suggesting that this model is broken. Social dysfunction, drug addiction and poverty plague many places that lack a sense of community. Sea level rise, extreme storms and repeated losses are making the sites less viable for long term occupation. Projecting out 30-50 years in these vulnerable coastal zones with relatively low population density, we needed to consider a more radical approach. Migration was our answer.

Through thorough analysis of GIS data on transportation infrastructure, demographics, population density, public health, hydrology, geology, and property loss from superstorm Sandy, our team recognized the opportunity to add density to underdeveloped upland transportation corridors. The proposal uses a systems-based landscape and urban development strategy. With our deep knowledge of city, state and federal regulatory processes, we created a more expedient and profitable development scenario for higher ground transportation corridors. This economic catalyst was paired with design of amenities to reduce commute time, improve housing stock, make walkable communities, and develop tight-knit mixed use neighborhoods.

« Understanding the cultural connection of people to places, we imagined a scenario where new denser transit oriented mixed-use neighborhoods on high ground would draw whole neighborhoods away from vulnerable barrier island properties. »

Understanding the cultural connection of people to places, we imagined a scenario where new denser transit oriented mixed-use neighborhoods on high ground would draw whole neighborhoods away from vulnerable barrier island properties. Beach houses, small businesses, public housing and the infrastructure that served them would over time be replaced by ecological and recreational landscapes, made more publicly accessible. The CLMZ would become a new ecologically rich area where different ecotones meet. Within this zone that stretches from Montauk down the Jersey Shore, a new mega-park would evolve at the scale of the mega-city. This regional ecological and recreational resource included already designated National Park Lands of Gateway, but also expanded to include the Meadowlands, new public beaches, temporal islands that only reveal themselves at low tide, and barrier reefs. The snakelike esker of Coastal Urbanism that borders the CLMZ would be the waterfront property of the future. To make this happen, people must move. The proposals were published in the 4th Regional Plan and policy makers listened. Governor Cuomo announced in January of 2020 a $275B infrastructure plan that can help make our plans reality.

What is needed is a combined strategy of this type of migration with adaptation and the development of host conditions that do not lead to degradation of valuable untouched ecologies. The 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on Climate Change and Land suggests that among our adaptation and mitigation response options, conservation of valuable ecosystems is more efficient than rebuilding.

« Examples of response options with immediate impacts include the conservation of high carbon ecosystems such as peatlands, wetlands, rangelands, mangroves and forests. Examples that provide multiple ecosystem services and functions, but take more time to deliver, include afforestation and reforestation as well as the restoration of high Carbon ecosystems, agroforestry and the reclamation of degraded soils.” (IPCC p 19)

Working in cities across the United States, I have seen how blind we are to the impacts of unchecked development. Sprawl is causing the extreme weather that people somehow find inexplicable. As a teenager in the early 1980s I suggested in my application to Dartmouth College that the biggest problem facing society was the loss of our natural lands. Now, over 35 years later, I have knowledge to envision how we can house people, grow food and sustain life without further destroying the planet.

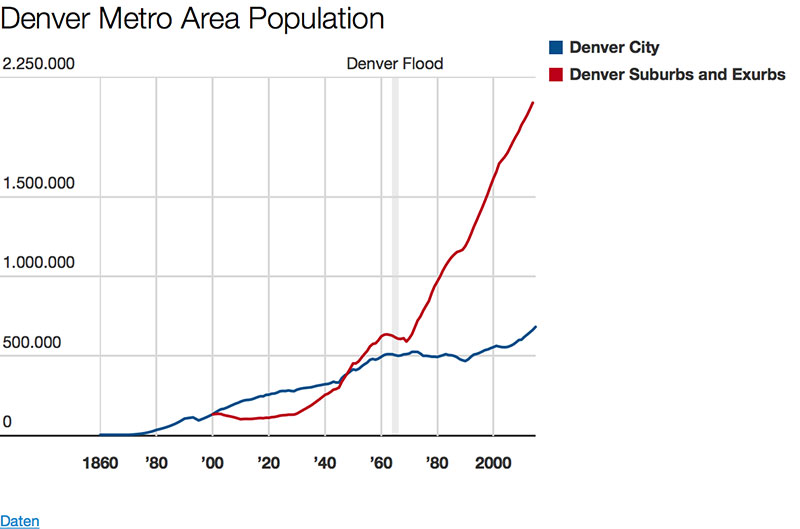

In the Fall of 2019, I made the decision to move to Denver Colorado, elevation 5,280’. My Brooklyn Heights neighborhood was safely on high ground in New York, but I wanted to explore how climate, development, infrastructure, and communities functioned beyond the Hudson River. The “Mile-High City” is one of the fastest growing areas in the country. Unfortunately, that growth is reflected in sprawling house farms, office parks and strip malls characteristic of the auto centered planning of the post WWII era in the United States. With very little public transportation, a dysfunctional Bus Rapid Transit program, and a downtown cleared by urban renewal and replaced by towers on plinths of parking, it is a car centered city. The result is that increasing traffic, poor air quality, and pedestrian safety are compromising overall quality of life. New walkable neighborhoods are emerging, but proposals for more and better public transportation keep getting shot down.

Migration to the State is happening, but unfortunately the need is being met by dispersed housing and development models that are major contributors of climate change. For all its natural beauty and sunshine, Denver was recently ranked among the top 10 US cities for air pollution with residents inhaling more than 260 days of elevated pollution over the last two years according to the EPA. Love of the car and lack of convenient alternatives are making Denver the new Los Angeles. Like many Cities in the United States, Denver’s core was gutted. In 1967, the Skyline Urban Renewal Program cleared 120 acres of the historic downtown buildings to make way for new office towers. As cars displaced trains, trolleys and other forms of mass transit, vast parking lots overtook the downtown district. Colorado attracts immigrants from all over the world, coming for the opportunities offered in the State including education, recreation, legal support for immigration, and a strong job market. What is needed in Denver and other cities gutted by auto-centric zoning policy is a push for greater density. When planning for major climate change impacts, designers and policy makers plan on 20-50-year horizons. Coincidentally this is how long it can take to design and implement major public infrastructure projects. Visionary politicians like Governor Cuomo are taking advantage of this alignment to enact the holistic change needed for a sustainable future.

As climate change is facilitating the need for greater human mobility, cities like Denver, Boulder, Cleveland, Detroit, St Louis, and others across the USA with underutilized urban centers can use this influx of people to catalyze urban redevelopment and add public transport back in their downtowns. Embracing density is very important. Walkable city centers, served by public transport, with affordable housing, parks, schools and cultural amenities of urban life are important for a more sustainable future. They present an opportunity for attracting people from some of the areas most impacted by climate change, with the goal of both humanitarian aid and urban redevelopment of downtown America.