An Unsolicited Manifesto for NewCities

June 2, 2014 — Blog

What could possibly warrant the existence of yet another foundation that cites ‘The City’ as the source of its legitimacy? Is the city really a cause that needs to be supported, to the extent even that it becomes the statutory aim of a non-profit organization? Somehow that notion doesn’t feel quite right. At the outset of the 21st century, cities thrive like never before, and it would seem strange that at the very moment of their apotheosis, cities would be in need of any kind of support.

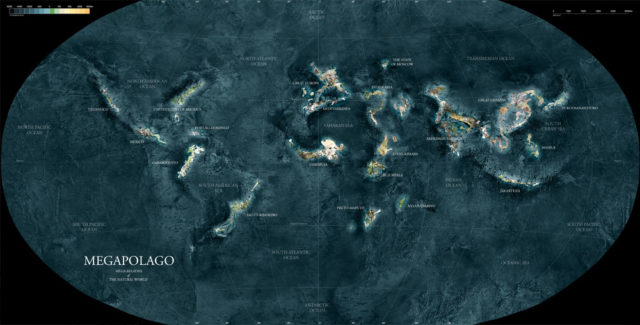

Cities flourish, because of us and often despite us. Certain cities now surpass entire nations, both in terms of population and the size of their economy: there are more inhabitants in Mexico City than in the whole of Australia; the GDP of San Paulo is larger than that of Sweden. If the current rate of urbanization continues, the world could be 75% urban by 2050, and close to 100% urban before 2100. Doxiadis’ grand visions of a Eucomenopolis could eventually prove a reality, and if they do, it will be the land left behind – the non-urban! – that will be in need of support.

Rather than dwelling on the city’s supposed needs, it would probably be more accurate to acknowledge that it is the very success of the city that motivates us: the desire to be associated with something that seems to thrive, almost regardless of our actions, and join in the momentum.

En route to becoming the only remaining form of human habitat on the planet, it is hardly surprising that the city is now the subject of an almost universal fascination: no longer the exclusive property of architecture, urbanism or planning, but the preoccupation of virtually every professional domain: technology, politics, sociology and business. McKinsey & Co is ‘planning’ cities in India; Siemens proposes large-scale urban infrastructure, generally as a precursor for Siemens trains; Shell works on the planning of Chinese cities, equipping them with Shell gas stations; and IKEA is methodically creating ‘meatball neighborhoods’ in Central London, full of Swedish Furniture. The digital world happily chimes in: Cisco focusses on Smart Cities, IBM on Smarter Cities, Oracle is the smartest, soon to be outsmarted by Google.

…More than ever, knowledge of the city equals knowledge of the world…

Even in the academic world, ‘the city’ is as an increasingly prevalent theme, the connective tissue that provides a common ground to otherwise hermetic and disconnected university faculties, a last resort for intellectual speculation. In a world that increasingly demands that education is useful (that great dirty word of the 1970’s) and prioritizes ‘applications’ over theory or critical discourse, cities have become the perfect alibi. Cities are the new studium generale: the program through which universities once cultivated a general sort of ‘knowledge of the world’ in parallel to the increasingly specialized programs of their individual faculties. With more than half of the world now living in cities (and the other half soon to follow) ‘knowledge of the city, more than ever before, equals ‘knowledge of the world.

Still, looking at the number of institutions which now generously offer their intellectual services to the city, one begins to wonder: who is being served by whom? The city has come to provide a sense of purpose in a post-ideological world for the commercial and educational sectors alike: private companies rely on the city for their business; academia needs the city for a meaningful application of its knowledge. It is the city that now sponsors the intellectual debate, rather than vice versa. The simple honest truth is that our relationship to the city is not one of authority, but one of dependency.

The shift from city to megacity must entail more than just an escalation of scale

Within less than ten years the world’s largest cities will all be located outside the west. Of the 33 megalopolises predicted in 2020, 28 will be in the world’s least developed countries. The metropolis, once the zenith of western civilization, is now the property of the ‘third world’. This shift has caused a deep sense of discomfort amongst the city’s protagonists; both the emergence of the megacity, as well as its predominant presence outside the west, are now mainly discussed in terms of crisis. It is interesting to observe how the change from city to megacity has created a distinct shift in the tone of the discourse. If the city is still presented with a sense of confidence, a showcase of human ability, the Megacity only registers with a sense of despair… an uncontrollable phenomenon; an unwelcome escalation; an onslaught on scarce resources; the overstretching and subsequent breakdown of all forms of infrastructure; the impossibility of any credible form of governance… Discussions on the megacity have become synonymous with the foreboding of an imminent apocalypse. Yet the shift from city to megacity must entail more than just an escalation of scale. If the megacity were simply a larger version of the city, this would not explain the wholesale panic with which it is received. What if the shift is more fundamental? What if what we portray as a crisis of the city actually serves to obscure a deep crisis of our understanding of the city and how we relate to it? What if we are not witnessing a crisis of the city, but actually a crisis of knowledge…?

If in the 1950’s the city was a still more or less controllable entity, broadly ‘obeying’ the doctrines of urban planning, the current megacity is like an organism. The panic displayed at the advent of the megacity is not dissimilar to the one displayed in the face of climate change or natural disasters…

We stand back and observe our own creation as if it were a fact of nature rather than of culture, which, at best, can be made to adjust course through a kind of ‘retroactive acupuncture’. Traffic bypasses, pedestrianized zones, deliberate amortization of certain quarters…, the same way a surgeon operates on the human body, we now perform ‘operations’ on the city, intervening in its internal workings and hoping for a better outcome. Congestion charge, emission tax, and other remedial measures are the urban equivalent to pain-killers or experimental medicine; piecemeal urban renewal the plastic surgery that keeps the city’s oldest quarters forever young…

So far the repertoire we have unleashed on the megacity has been mainly technological. (Not surprising, given that the city is the perfect business opportunity for tech firms.) However, by insisting that the megacity is a technological phenomenon, subject to ‘smart’ solutions, we have also reduced the megacity to merely a matter of problem solving. Thus we can safely resort to familiar reflexes of ‘help’ and ‘support’ without ever critically questioning our own position or actions towards the megacity. We are banking – once again – on the blessings of technology, while failing to see that the city in its present form is first and foremost the result of an escalation of technology.

At present there is no general theoretical framework that allows us to first understand our own relation to the megacity before we devise actions or remedies against its potentially negative consequences. Without such a framework we may well be contributing to the same problems we insist on fixing.

Rather than us thinking about shaping the future of the city, we have to allow the city to shape the future of our thinking

When it comes to the megacity, there is no monopoly in terms of knowledge. No single discipline can claim to hold all the answers. Only through a joining of intellectual forces can there be some hope of coming to terms with a phenomenon whose workings meanwhile defy any singular form of logic. Rather than us thinking about shaping the future of the city, we have to allow the city to shape the future of our thinking. Perhaps it is time to stop treating the city as the seemingly accidental topic of choice of various sciences or professional disciplines, but to emancipate it as a science in its own right. The city is the arena where almost all forms of knowledge are acted out: breeding ground, test lab and theatre of operation, simultaneously. Consequently, the city affects all domains of knowledge alike: the city is the sum of all –isms.

In bringing together experts from the fields of technology, energy, sustainability, infrastructure, telecoms, transport, finance, architecture, design, public policy and research, NewCities has made a unique contribution in recognizing this. It offers a platform for the academic- and the business world alike. Professionals and scholars, lecturers and audience, sponsors and actors convene in the context of a shared fascination. For all involved, taking part is not just a matter of reflecting on the current state of the city, but also a matter of self-reflection: the city not the object of help, but, ironically, also a rather compelling case for self-help… At times its conferences generate the charming feeling of a 12-step meeting: we simply form a circle and take turns in admitting that we have been holding up a front in pretending we are experts in the face of a subject which has yet to accumulate real expertise – united through the frank admission that we do not have a clue.

If the city itself is a place of exchange, which progresses only through a carefully crafted form of negotiation, then perhaps this is also the best principle for any kind of intellectual constellation that endeavors to address the city: a possibility of exchange between different (and potentially competing) forms of knowledge – a kind of intellectual bazaar where viewpoints are traded.

Perhaps the NewCities’ true genius resides in the fact that it is what it addresses.

All views expressed in the above article are entirely at the discretion of the author. They are intended to endorse the work of NewCities based on a personal interpretation of what the author sees at the Foundation’s mission. His views do not represent in any way an official position, political, or otherwise, held by NewCities.