Making Space For Justice

November 23, 2022 — Blog

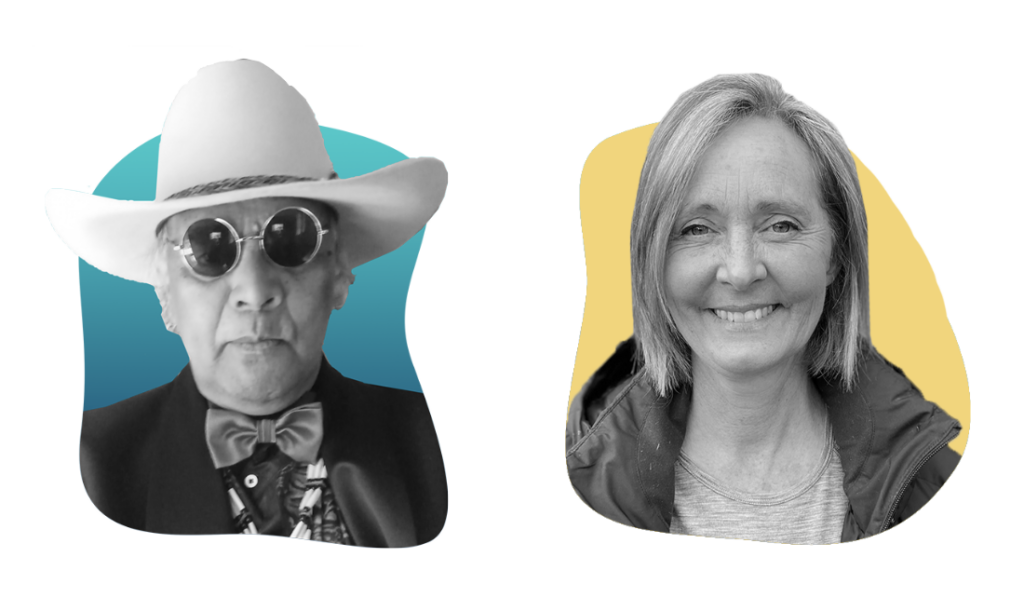

On a recent episode of threesixtyCITY, Associate Professor in Architectural Design at the University of Melbourne, Janet McGaw, spoke with multi-clan descendant, Elder, and activist Uncle Gary Murray on notions of spatial justice and equity in placemaking.

Uncle Gary Murray was born in Balranald, New South Wales. He is a multi-clan descendant of the Wamba Wamba, Dhudhuroa, Wiradjeri, Yorta Yorta, Baraparapa, Dja Dja Wurrung, Djupagalk and Werkgaia Nations which span across the northern parts of Victoria. He has over fifty-two years worth of activism around many First Nations issues in Australia, particularly in community development, native title, cultural heritage, economic development, and human rights.

Some of the transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Janet: Can you define the concept of spatial justice, and talk about how this differs from other kinds of justice?

Uncle Gary: Spatial Justice goes to the heart of colonization, invasion of all First Nations across the globe, and particularly in Australia. Spatial Justice addresses the issue of dispossession and dispersal, with all the genocidal connotations that goes with it. And we only have to look around today, in 2022, we’re sitting on the land of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people, language group. There’s eight clans in the extended family group, and probably six of those clans have gone forever. But there’s nobody around today that can claim those six clans’ country. So, that’s a snapshot of genocide in Australia, and that happens all over, not just in the province of Melbourne here.

People need to recognize that racial justice is about the tangible, and the intangible. It goes through intangible things like creation stories and astronomy, for example. The tangible part is land, water, and everything that leads to healthy communities. We need to get our land back, so that we can achieve joint sovereignty with the Australian government.

Janet: Aboriginal peoples or Indigenous peoples around the world have been disconnected and dispossessed from their lands. What’s particular about the Australian context?

Uncle Gary: Well, it goes through dispossession and dispersal. We were scattered all over the place. I come from a group on my father’s side called the Wamba Wamba group, and there’s probably way more Wamba Wamba people living in metropolitan Melbourne, which is not our country, than there are on Wamba Wamba country on the Murray River, Swan Hill, and Deniliquin terrain. So we’re scattered. And we’re trying to reconstruct our traditional communities with modern upgrades, as we say. You can’t do it unless you’ve got a land base, an economic base, a political base, a cultural base, and a moral base. We’ve got to bring back some of the old values that we’ve lost over the last four or five generations. And having a place that is ours, that we own, that we’re not leasing or renting, that’s really important. We need to get our land back. We’re lucky in Victoria, where we are. The state of Victoria has drawn a treaty path, and opened the treaty to address the sort of issues that need to be fixed after our lands were stolen.

Janet: So, Australia, unlike pretty well, everywhere else in the world, had no treaty when settler colonization began. It’s been a long process, hasn’t it, getting to the treaty?

Uncle Gary: Yes, it’s been over 233 years since the first white man stepped on our shores. We’ve got 270 First Nations language groups around Australia. In Victoria, we’ve got more than 38 First Nations; 300 clans in that 38 Nations. So clans are everywhere. They have the first rights of a country and any treaty should take that into account. And in one sense, it’s really good that we never drew a treaty when the white man first came here. Groups around the world, in Canada, and America, and New Zealand, went first. And whilst their treaties were done, some four hundred years ago, we learnt from them. We learnt from their failures and their mistakes, as well as the good things. So we’re in a unique position in Victoria; 38 Nations to construct a treaty that we design, that we determine, and that we negotiate directly with the state government of Victoria. I think that’s good in that sense.

Janet: That’s a really good point. I hadn’t thought about it like that. So do you think treaty is going to be a path to get spatial equity?

Uncle Gary: Well, one would hope so. We have a combination of cultural heritage strategies and land justice strategies in the state regime. And in those strategies over the last 25 years, and even the past 10 years, there is this responsibility to look after your cultural heritage; responsibility to get your Native title rights, and to get your fishing and hunting rights back. And then, with that bag of rights, there’s also what they call Crown land being transferred to Aboriginal title. And then a traditional land and management board is set up to manage a national park with the state and traditional land group within the park.

The next step is what can we do with those parks? And at the moment, in terms of land rights in the state, we’re lucky to own 25,000 acres in 7 million acres of Victoria. We’re a little black dot on a map of Victoria. With those Aboriginal title national parks, can treaty take it to the next level? And the next level is clearly what can we do inside those parks? Can we design and construct to create spatial justice inside those national parks? When the treaty gives us land back, we’ve got to look at those national parks and say, we don’t want the whole national park, we don’t want to restrict the national park to visitors and tourists. We need to be there, so you can see us. It’s a bit like that project in the Melbourne CBD. Where do you see us in the CBD? Well, you don’t see us because we haven’t got a flash building; we don’t have a culturally appropriate building that stands out, like the Eiffel Tower or the Empire State Building. We haven’t got that building in Melbourne CBD, but we need to build it. That’s still on the agenda. But we also need to satellite that concept across every one of the 38 plus Nations.

Janet: Uncle Gary, there’s been a lot of work done in the Architects Accreditation Council in Australia to transform the competencies that our graduates need to have before they begin working. About a quarter of them relate to understanding how to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. And some of those around how you might integrate Indigenous ways of knowing into the built environment and ideas of caring for country. How might those ideas change the way architects work on the kinds of projects that you’re describing?

Uncle Gary: Well, there’s several little things that architects can look at, like how do you build our space around water, fire, the stars, the land and the people. And you’ve got to come in with an open mind on that. And every First Nation, every clan is different. So you’ve got to come up with unique designs. And, you need to talk to the people on the ground, doing the cultural work and doing the everyday thing that we all do. And then you’ll get to where you want to go. Every design will be different, with the different country, different water, different astronomy stories and the rest of it. And you’ve gotta bring those intangible things into the space with your designs. And of course, the most important thing in 2022 is to make sure that it’s environmentally friendly, that we use really good materials that withstand bushfires, cause we get bushfires, and we get floods.

Janet: So you’re describing a kind of equity that mixes up the social and the spatial, is that right? That these things are entangled intrinsically for Aboriginal peoples?

Uncle Gary: They are. And, there’s an emotional component too. I bet when kids see a beautifully designed and managed building that it raises their self esteem. That’s ours, they can claim it. We’ve got to build people’s self esteem, from our kids, to our elders, and everybody in between. And that’s what we’re all about. It’s not about the 233 years of dispossession and dispersal. We’re trying to address that so we can move on. We want to move on. We want to share this country, I suppose. We have a shared history up to a point, some good, some bad, some beautiful, some ugly, but at the end of the day, we’re here and nobody’s going home. So at the end of the day, we need to sit down and get that spatial justice sorted out. Between all the strategies, and now the treaty, we have the perfect opportunity for this generation to build the satellites we’ve talked about in the Melbourne project.

Janet: So what role do you think non Indigenous allies can best play to support projects like the ones you’re talking about and Indigenous placemaking more generally?

Uncle Gary: Get behind the strategies and the concepts we’re talking about. You need the experts, and mostly non-Aboriginal experts. You got to bring them in and work out your joint strategies and how they fit in. Everybody has a role in addressing the reconstruction of our communities, and getting the design and construction concepts together. Plumbers and electricians, we need them too. It’s a team effort, and you’ve got to put your best team on the field, and it’s not a color problem.

Janet: What do you think a spatially just world would look like, Uncle Gary, and how do we get there?

Uncle Gary: Well, the process is doing the design and construct concepts in every First Nation, and getting our kids involved in it so not they’re not in the streets getting shot, or bashed to death. We’ve got to get them in safe environments, and we’ve got to build their self esteem up, and educate them, and give them skills development training, and make them proud of their culture. If you look behind me, I’ve got my daughter’s artwork up there. We’ve got to start raising that culture. People need to see this stuff, people have to go to a space, go to a website, and see their ancestors up there. And not just photos, but the story about those people. That story also has to be built into the bricks and mortar stuff. So when you walk past that building, you know it’s us. When you walk inside that building, you know it’s us. And that’s what the kids have to see, and the elders have to see before they die.

You’ve been working on this stuff with huge energy and enthusiasm for so long, Uncle Gary. Just help us understand what motivates your activism?

Uncle Gary: Well, I come from a long line of activists. My grandfather was a very prominent person, important in the state and around Australia. He was knighted by the Queen and made cabinet of South Australia. So, he went to a new level. He’s the only one who’s done it, nobody else has done it since. My dad, of course, Stewart Murray, he was mentored by my grandfather back in the day. We’ve come from that, we come from hunters and headmen and head women. So we’ve always been out there doing stuff. That won’t change ever. All my kids, I’ve got twelve kids and every one of them are out there doing stuff politically, having a go and doing the right thing. And the grandkids are gonna be even better, they seem to be getting taller, better looking and smarter. And I’ve got 28 of them. So I’ve got a little army going there. And I’m looking forward to them really taking a big role in the community. And maybe I’ll go fishing then, but not now. I’m still here, and I intend to go for a bit longer. I want to see stuff done. It’s unfinished business.

Janet: You’ve talked about some projects that have gone ahead, Indigenous cultural and knowledge and education centers in regional Australia. Tell us about those and how they’ve benefited communities there.

Uncle Gary: Right, well we’ve got the one in Gunditjmara, where four of my kids come from. But that was probably the one that got the most attention around its design. The Gunditjmara people are the eel people, they farmed the eels. They controlled waterways so the eels came into a certain channel, and they just picked them up, smoked them, and traded and ate them. So, they’ve created, probably a multimillion dollar building, that’s built around that, the eel nets and the stone huts that were there before the white men came to the zone. So everybody’s got their own ideas about what sort of building can be done, right into environmentally friendly stuff as well. Really good, unique designs that reflect their culture.

Janet: Settler Australia has tended to focus its interests in really concentrated areas, like the capital cities, located around the fringe of Australia, mostly in the southeast, and a little bit over in the West. Aboriginal people occupied the whole of Australia, prior to colonization. There is a kind of different spatiality at play, and I’m wondering, is that part of why these satellite centers that you’re talking about are so important?

Uncle Gary: Well, they’re important because each nation has a country and each nation’s got social issues, economic issues, political issues, and they need a base, a modern day base, and obviously the multi-purpose concept is what we all look at. The days of just putting a building up with boomerangs on the wall are gone. We want a place to live that’s safe, culturally relevant, and reflects us. Each nation, each clan, will want that. And it’s really important that we get the resources to do it, whether it’s with the Native title outcomes or with treaty outcomes, whether it’s state treaty or national treaty.

Janet: So do you think that architects should seek out these groups for any project they’re working on, regardless of whether it’s a project specifically for Aboriginal cultural interests?

Well, that’s the good news. Because it’s called planning, and planning can be good or bad. Good planning is when you get architects and lawyers and economists together to provide assistance to win contracts, to transfer money to do what we need to do. Look, there aren’t too many buildings done yet. We’ve done a handful, but there’s probably another 30 out there that need to get done. There are multimillion dollar concepts that need architects to come up with good designs and give us a master architectural plan, then get into the actual design and construction of the building and the rest of it. So it can create its own industry, if it’s done properly and respectfully. That’s what we ask.

Janet: So you’re suggesting people reach out to communities, find out what they need, and gather together groups of other professionals who might have skills to advance those projects. Is that what you’re saying?

Exactly, whether it’s an individual company, or a group of companies, let’s work a strategy out. If you contact me, we can talk about an architectural strategy for the Murray River from the top right to the bottom. Cause there’s no real buildings there. And we’re all in the process of Native title, cultural heritage, and treaty. So the option’s now, get in there, and provide the important participation and respect, and it will be a two way thing.

Janet: Some traditional owner groups are from areas that have been more intensively claimed, and built on by free settlers in the early days, when that strange notion that you could just arrive and take what you wanted for the first 20 years or so of settlement and colonization in Victoria. And those lands are the most difficult to get back. So can you talk about the challenge of groups that are in areas where there is not much Crown land at all? And how they might actually get land justice?

Well, the only Crown land left now is surplus assets that the police don’t want for example. And, the usual thing is, the state transfers that over to a Native title group to try and settle that. And the only other way we’re going to get land back is to buy it back on the commercial market. So if we’ve got traditional owners living in Melbourne, who aren’t Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung or aren’t Boonwurrung, and they don’t want to go home, their treaty rights and benefits shall be allocated to them in Melbourne. That means providing funding for housing development or business development. There are 25,000 Aboriginal people living in Melbourne right now, and there are only about 2000 that are traditional owners from here, the rest are from all over the country. And some of them will never go home, they’ll probably be in these parts for generations. So if we’re gonna give them treaty benefits, then there should be an option of giving those benefits where they live. That’s a new thing that is going to be hard to win, but I don’t see a problem with it.

Listen to the conversation on our threesixtyCITY podcast.