Why New Cities Need Sustainable Transport Planning

November 13, 2014 — Blog

“An advanced city is not a place where the poor move about in cars, rather it’s where even the rich use public transportation.”

Enrique Penalosa, Mayor of Bogota, 1998-2001

I applied to the Impact King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) Fellowship because I am extremely interested in the challenges and opportunities of designing and implementing a sustainable transportation strategy from the ground up. The Impact KAEC Fellowship offers me the chance to combine my professional experience consulting for various transportation agencies in the United States with my recently completed degree in urban planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

For my Master’s degree, I focused on sustainable transportation and infrastructure, particularly in rapidly developing foreign countries. As part of my research, I visited Colombia in spring 2014. In Medellin, Colombia’s second largest city, people move about on the Medellin Metro, the country’s only metro system. The transportation network is bolstered by the Metrocable, a gondola lift system that serves impoverished hillside communities, previously only reachable by slow and infrequent microbuses. In Bogota, the TransMilenio system has defined what Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems can accomplish, and as a result, has captivated the world. Many other cities, such as Guangzhou, Rio de Janeiro, and Lima have since implemented systems that build on Bogota’s success.

These are inspiring examples of what a successful, innovative transportation system can do to transform economies and elevate the quality of life in our urban habitats. However, in the case of new cities, the challenge remains – should a modern transportation system be implemented before or after people begin moving in?

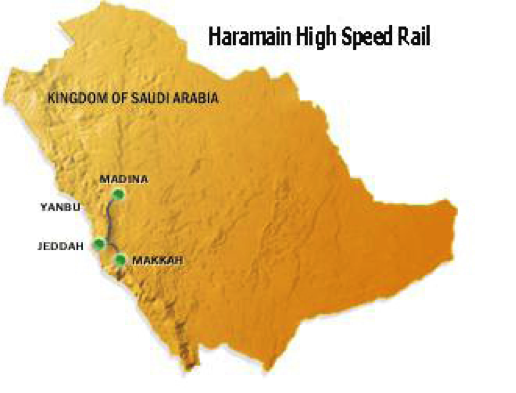

As an Impact KAEC Fellow, these are questions that I am hoping to explore, putting my recent experience in Bogota and other cities to use in a major new Middle Eastern City. King Abdullah Economic City, my home for the next six months, is a vast new city being built on the coast of the Red Sea. When finished, KAEC will cover 67 sq miles – that’s nearly 2.5 Manhattans – and hold an expected population of 2 million. This population will temporarily surge each year for the annual Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. Hajj brings over 3 million people to the Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia, home of Jeddah, Mecca, and Medina. The former is the commercial heart of the region, and the latter two are the holiest sites of Islam. A high speed rail system is being constructed to connect Medina, KAEC, Jeddah Airport, Jeddah City Center and Mecca to meet growing demands for better transport for the influx of pilgrims annually, as well as Saudi residents. The high speed rail line is scheduled to open within the next few years, connecting the area and offering an alternative to road transport for visitors and Saudis alike.

The role of a sustainable transportation system in KAEC plays an important part in how the city functions as well as KAEC’s role in the region. As an economic city, the aim of KAEC is to provide housing, jobs, and entertainment all while maintaining a high quality of life for Saudis. However, today in Saudi Arabia, oil is inexpensive and the car is king. Why would residents wish to change their habits? KAEC represents a unique opportunity to serve as a beacon for what a quality transportation system could be, built from the ground up. In order to successfully lure people from their cars, KAEC’s planned transport system needs to be reliable, quick and attractive – in short, a seductive alternative to cars when it comes to getting from point A to B.

How will KAEC ensure this happens? Transportation and infrastructure has traditionally been in the realm of civil engineers. In order to achieve success, I argue that the planning of a sustainable new transport system needs to become a holistic part of an ecosystem, in concert with housing, jobs, and changing and evolving demographics.

While it might be rational to suggest that international “best practices” be applied immediately to KAEC, the answer might not be so simplistic. Innovative transportation solutions have never occurred in a bubble; rather, the strategies that led to success in other parts of the world occurred within the political, spatial, and socioeconomic context and constraints of each city and region. In the case of KAEC, the eventual implementation of a sustainable transportation should be flexible. The difficulty is that infrastructure is expensive and has traditionally taken a long time to build and implement. A transportation network should first and foremost serve the needs of the people. How can builders and planners of a new city such as KAEC predict what these needs will be in 50,100 years’ time? This is where we come to the chicken and egg conundrum: this new city needs a forward-thinking infrastructure plan, but the future behavior patterns of the city’s projected population cannot be fully predicted. How can we solve this conundrum? In the case of new cities, the changing and evolving population requires a system that is capable of change and evolution as well. Ideally, a partnership between traditional development and real estate firms, economic interests, institutions and local government is essential to implement a system that will directly impact how people live, work, move and go about their daily activities, while reducing environmental impacts and elevating quality of life.

I’m truly excited to be starting out my Fellowship in KAEC and to have the opportunity to contribute knowledge about transportation solutions for new cities, not only for the benefit of future residents, but for other cities and regions worldwide that could learn from KAEC’s developments.