A Contract for Public Good: Urban Data in the Digital Age

November 10, 2016 — Blog

I confess: I am a data enthusiast. An evangelist even. Urban data is the currency of the 21st century. A catalyst for creating more livable, sustainable and equitable cities in an age of rapid urbanization. Working from within local government, I have seen first-hand how having a good handle on data can transform public services and policies, create new business models, and improve citizen satisfaction. Data offers greater accountability and efficiency while bringing new stakeholders to the table to solve the challenges facing our communities. It inspires those working on the front lines with the tools they need to make our cities better. As new on-demand mobility services and autonomous vehicle technologies ignite a global conversation about urban form, policy, and access, data will reign now more than ever.

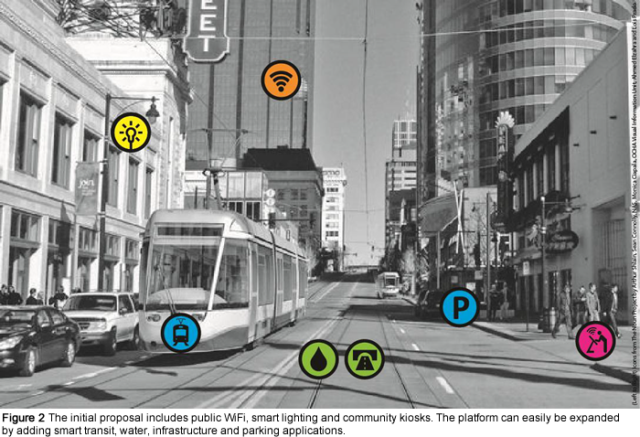

Before I started working inside city hall, I must have intuitively understood the importance of data in the digital age. As an architect, I saw how design feedback loops can improve buildings and allow for flexibility. As witness to the true potential of data in both Kansas City, MO and Los Angeles, CA, however, I am convinced that we must consider that data is essential to any issue – social, economic, or physical – within our cities. It’s as important as the roads we build or any service we provide. Local governments are increasingly embracing communication infrastructure, the Internet of Things, and data analytics as tools to build better communities for citizens.

But as powerful as data can be, data for the sake of it is ineffective. It cannot inform better outcomes if local government lacks the capacity to analyze and respond to the information it provides. Collecting data when there is no business case leads to greater risk of unnecessary breaches, overwhelms decision-makers, and offers no new benefits. Public concerns about security and privacy are legitimate and need to be addressed transparently from day one. Government (at all levels) must be stewards of data and take steps to improve accountability, adopt best practices, fund the necessary infrastructure, and continuously train its workforce to handle the expanding responsibility of public information.

Government should also consider asking for permission and explain what is being collected and why. In democratic and participatory governments, we must forge a new social contract that builds on our liberties through the protection of our government. As consumers, we generally don’t think twice about clicking through the terms of service on a smartphone app or website that collects our data and tracks behaviors for commercial use. And yet the public sector is far more hesitant when facing the challenges of big data.

City leaders need to engage in direct conversation with constituents to understand the threshold between public good and individual privacy. For instance, would you be willing to share your travel behavior if it meant better incentives, a reduction in congestion and improvement in air quality? Perhaps not everyone is willing but what about giving the citizens the choice to opt-in to support these efforts? As an example, for local governments to get a better handle on how mobility behaviors are changing, we will need more than manual traffic counts and loop detectors to assess the changing ecosystem of services.

In central levels of government, we should still ask the question: What issues are we trying to address – what are the priorities of the city? This is about understanding how data can help drive better outcomes. Data creates a level playing field by allowing more participants to address some of our most critical issues and eliminating our personal bias in understanding. So, how might governments partner with new stakeholders – nongovernmental organizations, academia, and the private sector – to address our biggest challenges through data sharing?

To start, all governments must reflect and design policy frameworks that articulate the purpose behind data collection, provide protection for the individual, and allow for change if something is not working. The public sector must embrace the incredible potential for data to inform new methodologies, engage new partners, and leverage new resources to make our cities more livable, sustainable and equitable. As citizens, we must all ask ourselves, what am I willing to share to contribute toward a better tomorrow?